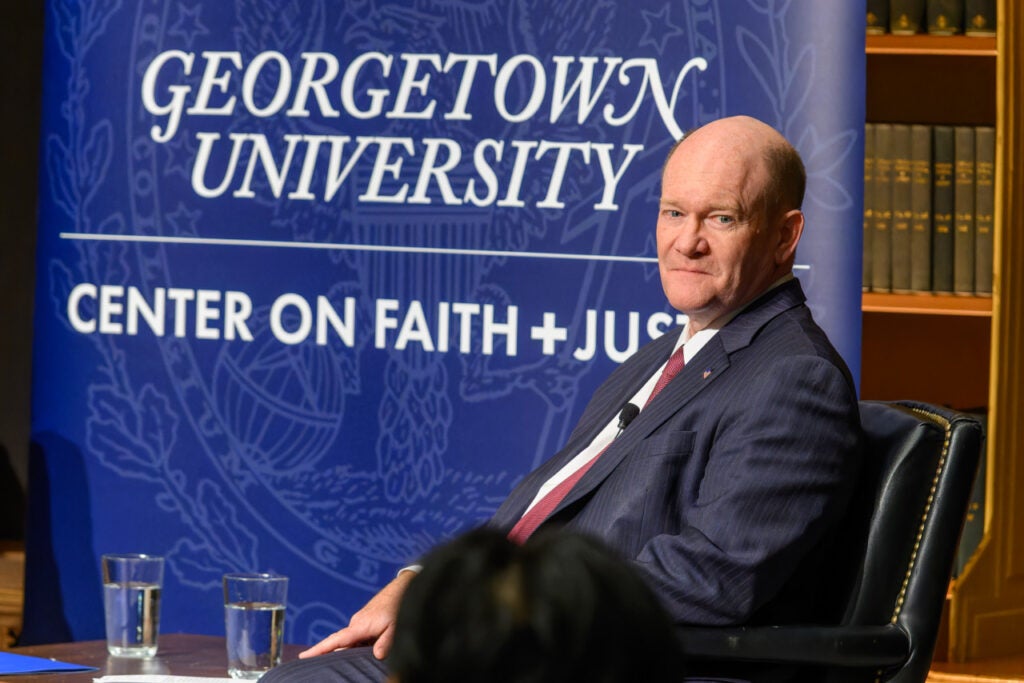

Senator Chris Coons spoke about how his Christian faith has shaped his life and helped him forge friendships across the political aisle during a candid and deeply personal conversation with students, faculty and staff at Georgetown on November 28.

The senator from Delaware was hosted by the Center on Faith and Justice as part of its “Higher Calling” series, which brings political leaders to the Hilltop to engage in conversations about the role of religion and ethics in their public and personal lives. The first guest speaker, in March, was House Speaker Emeritus Nancy Pelosi.

Coons, who as a youth attended the Red Clay Creek Presbyterian Church in Delaware, completed his graduate studies at Yale Law School and Yale Divinity School at the same time, while volunteering with groups in New Haven that help homeless persons.

“Chris Coons is a public servant who knows what the phrase ‘higher calling’ means,” said the Rev. Jim Wallis, who moderated the conversation. Wallis is director of the Center on Faith and Justice and the Archbishop Desmond Tutu Chair in Faith and Justice at the McCourt School of Public Policy.

During the November 28 event in a packed and festively decorated Riggs Library, Coons spoke about how his parents modeled an active and inclusive faith, why he decided to enter politics instead of the ministry, and offered advice for students looking to bridge differences on campus and considering careers in politics.

“We need you more than ever. American democracy is genuinely in trouble,” Coons told the students. “We are really having trouble as a country respecting each other, hearing each other.”

“It is my hope that some people listening will decide that being engaged in the work of democracy is worth their time,” the Senator continued, “whether that’s in an elected role or in their neighborhood, through civic organizations or just through how you treat others in your dorm or the hallways or in your classes.”

Coons credited his parents with showing him how to put his Christian faith into public service. His mother has helped settle refugees and his father was active in prison ministry, becoming particularly close to a man named Paul who was convicted of murdering his own abusive father. Years later, Paul told Coons that his father’s trust and kindness changed the trajectory of his life.

“That had an enormous impact on me,” the senator said. “That my father took that risk for someone he had no connection to. For both my parents those actions were the ones that taught the most to me about defining ‘who is your neighbor’ and broadening the circle of concern beyond folks who speak the same language as you or look like you or have the same background or life trajectory as you – and that was because of the faith of our church.

“That kind of quiet, humble service challenges me because I am in a career where hanging a lantern on what you do is given higher priority than what you actually get done,” Coons said.

During law school, the future senator said he felt a calling to explore his faith more deeply. “I met a wide range of people from a variety of different backgrounds trying to make a difference in the world and the common thread across many of them was faith.”

The senator said he considered entering the ministry and that his stepmother “prayed I would lose an election so that I would accept my calling to the pulpit.”

Though Coons continues to preach and perform weddings, he decided on a career in politics, winning an election to the U.S. Senate in 2010. There, he has made bi-partisan friends through the weekly Senate Prayer Breakfast, one of three places – the others being foreign trips and the Senate gym – when senators can gather, without staff or media present, and be themselves, he said. Every Senator is required to speak for 20 minutes about their own faith. He told the story of his father welcoming Paul into his childhood home.

“If you are willing to be open to each other, with almost all of my colleagues, you can find a way toward relationships and working together,” Coons said. “A large problem with getting things done because of lack of trust and the lack of trust is because we spend no time together.”

Coons said he faced a religious dilemma when he chaired the National Prayer Breakfast in 2017, shortly after former President Donald Trump took office and initiated a ban on immigrants from several predominantly Muslim countries, including a family of Syrian refugees that Coons’ mother had worked to bring to Delaware.

Coons said he struggled to decide what to say to Trump, who, as is customary, attended and delivered remarks at the prayer breakfast. Privately, Coons said he challenged Trump to rescind the ban. Publicly, he prayed for the president, a gesture that earned the senator considerable political criticism.

After reflecting, Coons said, he told people: “What part of ‘love your enemies’ did you not understand?”

During a Q&A with students in Riggs, Maggie Lober, a constituent of Coons’ from Delaware and a second-year student in the Walsh School of Public Service, thanked the senator for sharing his experiences.

“I was especially moved by the importance of the conversations that you’ve had with your colleagues and holding yourself open to conversations across the aisle with people who you don’t ideologically agree with,” Lober said. “And it strikes me as very important, especially in a university setting, to make sure that we are holding ourselves open to those conversations as well … What advice would you give us for making sure that we are holding ourselves open to experience all of those diverse perspectives?”

First, put your smartphone down, Coons suggested.

“These are profoundly divisive,” he said, holding his phone up. “I spend too much time doom scrolling, looking at stuff that’s not constructive. And it does something to relationships to only communicate through text and to only see people through social media.”

His second piece of advice was to gather regularly with people with whom you may not always agree. “I think spending time with people is a challenge and an opportunity and ultimately a blessing. And if you aren’t spending time with people from significantly different views and backgrounds and listening more than you’re talking, you may not be fully open to other people’s perspectives.”

Tomas Buccini, another student from Delaware, said one of his favorite aspects of Georgetown is the liberal arts education that requires to take classes in the humanities. Reflecting on his own Quaker education and his recent reading of Immanuel Kant’s essay “What is Enlightenment,” Buccini asked Coons what role universities should play in forming their students’ spiritual lives.

“I think the spiritual formation of students is essential to their education, to their ability to live full and meaningful lives,” Coons said. “Institutions that have a rich sense of a faith tradition and provide a wide range of opportunities for students to reflect on what they are called to be and who they are meant to be are more successful at education.”

Each university must determine for itself the tools and resources by which it forms students, the senator said. But being educated means wrestling with deep questions such as: are humans creations or creatures? That is, are we made by God, or not?

“How can you be educated and not wrestle with that question?” Coons asked. “And so an institution of higher learning that doesn’t wrestle with that question and does not support and facilitate wrestling with that question is a trade school. It is providing you with the mechanical schools to be successful in a career, and there is nothing wrong with that, but that’s not a university.

“I don’t know if I answered your question,” Coons told Buccini, “but you are on the right track and so is a university that welcomes and cherishes students that ask questions like that.”